The Canadian people, and most certainly Canadian children, are almost continually subjected to Aboriginal Industry propaganda, a pillar of which is the historical narrative whereby murderous, thieving Europeans impose ‘genocide’ and violence on the innocent, saintly and otherwise virtuous aboriginal inhabitants. While not wishing to belabour the point, we still feel compelled to occasionally present some historical balance...

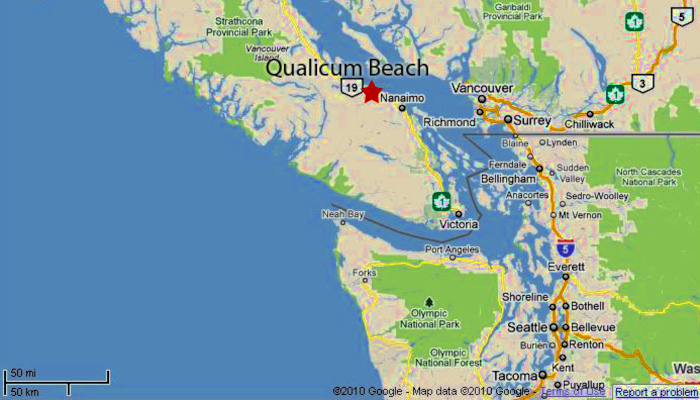

“When you drive over the Big Qualicum concrete bridge, 106 miles north of Victoria on the Island Highway, the scene is peaceful enough. But you are within bow-shot of one of the most chilling massacres in the blood-stained annals of Indian tribal warfare on the Pacific coast.”

“The historical name of the Indian village at the mouth of the Big Qualicum River was Saatlaam or Saat-lelp, meaning “the place of the green leaves“.8 This was the site of an infamous mid-nineteenth century massacre, which saw the majority original Qualicum Indian Band butchered by a war-party of Haida Indians, the remainder carried off as slaves.

“A witness to this atrocity was a party of Hudson’s Bay Company explorers, led by twenty-six year old Adam Grant Horne, who are believed to be among the first ‘white’ people to have contact with this district.

“Horne recounted the tale of the massacre to W. Wymond Walkem in 1883, some twenty-seven or twenty-eight years after it took place. Walkem published the account in 1914.9 Horne told Walkem that he had been charged by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1855 “or thereabouts” to lead a party of six men up the east coast of Vancouver Island to ascertain whether a trail existed from the Big Qualicum River to the head of Barclay Sound on the west coast of the Island. He was told by Roderick Finlayson, the H.B.C. official in charge of Fort Victoria, that the natives living near the mouth of the Big Qualicum were believed to be of the same tribe as those at Cape Mudge.

“Horne and his men approached the Big Qualicum in the very early hours of the morning and put in to shore about a mile south of the river’s mouth. At about six o’clock, Horne was awakened by one of his men, who in a silent gesture pointed out the boat-loads of Haida Indians entering the Mouth of the Big Qualicum.

“We were fully awake without any loss of time and from the edge of the timber, we saw these large northern canoes enter the creek one after the other, and disappear behind the brush which bordered the banks of the stream. Then we took breakfast, and while doing so, thick volumes of smoke arose from the creek and poured down across the front of the timber where we lay concealed.

“We waited patiently to see whether those [Haida] Indians would return or not. It was fully twelve o’clock before the first of them came into view in the lower reaches of the creek. We were horrified at the antics of these demons in human shape, as they rent the air with their shouts and yells. One or two of those manning each canoe would be standing upright, going through strange motions and holding a human head by the hair in either or both hands... In an hour’s time, they were all out of sight behind a bend in the shore line. There was no doubt in our mind but that we were about to face some dreadful tragedy.”

“Horne and his men entered the Indian village and found that the Qualicum Band had been annihilated. Most had been murdered and mutilated. Only one old woman was barely alive when the H.B.C. men arrived and, before she died a few moments later, she gave a brief account of the massacre.

“They had all been asleep in the large rancherie when the Haidahs crept in with stealthy step, and more than half of those asleep were killed without awakening. The remainder were quickly killed, there being five Haidahs to one of themselves. She was wounded with a spear, but had seized a bow and fled to the side of the creek and had hidden herself beneath the bank. The Haidahs had taken away with them two young women, four little girls, and two small boys. This expedition was in revenge for the killing of one of the Haidahs when attempting to carry off the daughter of one of the principal men who live where the death currents meet (Cape Mudge {Quadra Island}).”

–‘INDIAN AND NON-NATIVE USE OF THE BIG QUALICUM RIVER: AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE’,

Brendan O’Donnell, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Native Affairs Division Issue 9:

Policy and Program Planning, September 1988

https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/library-bibliotheque/112600.pdf

Footnotes:

8. (Robert Brown), Vancouver Island. Exploration. 1864. Victoria: Printed by authority of the Government, by Harries and Company, (1864), p. 25. A microfilm copy of this booklet is included in: “Western Americana: Frontier History of the Trans-Mississippi West 1550-1900“. New Haven, Conn.: Research Publications Inc, 1975. Copy on file at the National Library of Canada, Mic. C-13, Reel 75, No. 753.

9. W. Wymond Walkem “Mr. Horne’s Trip Across Vancouver Island“, in “Stories of Early British Columbia”. Vancouver: Published by News-Advertiser, 1914, pp. 37-50.

See also T.W. Paterson, “Massacre at Big Qualicum“, in ‘Ghost Town Trails of Vancouver Island’. Langley: Stagecoach Publishing Col., 1975, pp. 89-94.

“Before the arrival of Europeans, the Haida were the dominant culture among coastal ‘First Nations’ {Indian tribes} in Canada’s Pacific Northwest, and their unique war canoes were a key reason.

“With plentiful food and towering evergreens on Haida Gwaii, the natives there had the time and resources to develop a boat like no other in the region. Their canoes were the only ones capable of crossing the 60 miles of Hecate Strait between Haida Gwaii and the coast, allowing them to raid and trade with mainland villages — without fear of counterattack — and range from present-day Alaska to Vancouver.

“The Haida also had a size advantage: Thanks to their protein-rich seafood diet, the average Haida man in the 1700s stood 6 feet tall and towered over mainland natives and most Europeans.

“A lightning raid by a fleet of Haida canoes would have been terrifying. Each boat was filled with two dozen hulking warriors in wooden helmets and war coats of thick sea lion or elk skin, armed with painted war paddles (points sharpened to a spear, edges shaved to a blade), and chanting battle cries. Early European sailors called them the “Vikings of the Pacific Northwest”.

“Haida canoes were made from a single carefully-picked cedar. Felled in the fall, the tree would be burned and carved over the winter into a dugout as large as 50 feet and 3/4-inch thick. The Haida design made two key two changes to the traditional dugout canoe. The bow and stern were raised and given long overhangs, and the sides were flared outboard by filling the dugout with water, steaming it with red-hot stones and pushing the gunwales apart with branches.

“The result was a graceful 1.5-ton canoe able to hold as many as 40 people and navigate large seas without swamping. Haida paintings added to a canoe’s appearance. A singer/drummer in the bow kept time for the paddlers, and an oarsman in the stern steered. Each canoe typically carried a shaman or medicine man to catch and destroy the souls of enemy warriors in advance of battle.

“Haida women also were skilled boat handlers and sometimes went to war alongside the men. Feared among mainlanders, they typically came for vengeance and fought more savagely than the men.

“The land tribes, if they saw a Haida canoe with a woman in armor in front or a canoe full of Haida women, that’s when they’d say, ‘Let’s run!’ The women would be there for revenge”,

says Sean Young, a watchman at the ‘SGang Gwaay’ World Heritage Site on Anthony Island.

“The Haida had an oral culture, and the skills to build these canoes were lost during the smallpox epidemics that almost annihilated the tribe in the mid-1800s. Revival of the modern Haida canoe is credited to the contemporary Haida artist Bill Reid, who studied the original canoes in museum collections.

…”

–‘The Haida Canoe and the Vikings of the Pacific Northwest’,

Stephen Blakely, Soundings, Feb. 28, 2015

https://www.soundingsonline.com/news/the-haida-canoe-and-the-vikings-of-the-pacific-northwest

“WHEN YOU DRIVE over the Big Qualicum concrete bridge, 106 miles north of Victoria on the Island Highway, the scene is peaceful enough. But you are within bow-shot of one of the most chilling massacres in the blood-stained annals of Indian tribal warfare on the Pacific coast.

“A handful of ‘white’ {European} men camped less than a mile away watched the raiders come anal go and were at the scene of the tragedy a few hours after the slaughter occurred.

“The story is told by the historian of early days in B.C., Dr. W. W. Walkem, after a talk he had with Adam Horne, chief factor for many years for the Hudson’s Bay Company at Nanaimo.

“In May, 1856, when he was a young man of 25, Adam Horne was selected by Chief Factor Finlayson of Fort Victoria to find a trail across Vancouver Island to the west coast. The factor told the young Scotsman that it was a dangerous mission; the natives were not well-known to the company but their relatives at Cape Mudge, the Euclataws, had a very bad reputation for treachery and theft. If the Qualicums refused to give him any information, he was to leave their camp at once and use his own discretion in completing the assignment.

“The party was selected with great care, the factor appointing a French-Canadian named Cote as the guide because he was a good canoe man, knew the waters of the coast thoroughly and didn’t know fear. The interpreter was also selected by Finlayson.

“The young Scotsman noted that he had a great but profane flow of language, but as it was always in French, it didn’t shock him too much. One of the four men Horne was allowed to choose was an Iroquois, an old “engage” of the company.

“The little party left Hudson’s Bay Company’s wharf at the foot of Fort Street before dawn in a Haida-style canoe, roomy and light and rising like a duck on the whitecaps outside. On their way north the party called at Salt Spring Island and passed a large number of Cowichan Indians, fishing. They ran on a mud flat five miles south of their objective but soon got off again. They now lit no fires and took every precaution to keep concealed as they believed they were in hostile country.

“From a sound sleep in a snug cove protected from the Qualicum or west wind, which was blowing hard, Horne was awakened by the Iroquois with a finger on his lips. He said he had been scouting around and they were within one mile of the Qualicum and he had been watching for some time a large fleet of northern canoes approaching the creek mouth. From the edge of the timber in which they were hidden, the ‘white’ men watched the canoes enter the creek one after the other and disappear.

“While they were breakfasting, they saw thick columns of smoke arise from the creek and pour into the timber in which they were concealed. They lay from 7 ’til noon before they saw the first of the canoes come out of the creek. The Haidas in their great war canoes were war-whooping in triumph, one or two of them standing upright and holding a human head in his hands by the hair.

“The wind was blowing a near hurricane from the north but the Haidas hoisted mats for sails and were soon flying before the gale. In four hours, they were all out of sight.

“The little party of watchers allowed another hour to go, then struck camp and poled their way along the shallow beach ’til they came to the mouth of the Qualicum, which they entered from the north. Very cautiously, they worked their way up the river against a swift current. Bush cut off their view and they proceeded very cautiously with their loaded muskets at their sides, ready for instant use.

“They had seen nothing yet of the Qualicum rancherie but volumes of smoke were pouring still from one side of the stream.

“Shortly, they rounded a bend and were stricken dumb at the scene! The rancherie was a heap of blackened timber, still burning. Naked bodies could be seen here and there, lying in the clearing surrounding the rancherie. There was no sign of any life.

“The interpreter called out that they were friends and there was nothing to fear but there was no answer. Then, very cautiously, they walked over to the bodies to find to their horror that they were all headless and fearfully mutilated. They searched everywhere for a living human but without success.

“While they were discussing the problem, the Iroquois suddenly left them and walked diagonally towards the bank of the creek. Then he halted, with his head cocked to one side, like a robin listening for a worm in the lawn. He stood like that for several moments and then, in his moccasins, glided towards the creek. There, he lay down with his ear to the ground. Rising at length, he went a few yards farther down the creek and lay down again with his ear over the edge of the bank beneath an overhanging maple tree. Extending his arm, he bent it under the bank and drew out the naked body of an Indian woman. She was a fearful sight, old and wizened, but still clutching a bow in her dying grasp. She was chanting a dirge in a low monotone and it was this the Iroquois had heard.

“She had a spear wound deep in her side from which blood was pouring. Her face was bloodless and she was too weak to offer any resistance but after many attempts, in gasps and between long pauses, she told the elf-locked interpreter the story.

“They had all been asleep when the Haidas poured in from the river after beaching their canoes soundlessly, and more than half of the little tribe were killed before they were awake. They were lucky. The others were cruelly killed because there were five Haidas to every Qualicum.

“She was wounded by a spear but she had seized a bow and fled to the creek where she hid beneath the bank under the roots of the giant maple. She said that after killing all the grown men and women, the Haidas had taken away with them as slaves two young women, four little girls and two small boys. She whispered that the Haidas had massacred the tribe because one of the northern warriors had been killed at Cape Mudge when he had tried to carry off the daughter of one of the Euclataw chiefs. The Euclataws were too strong for the Haidas but the Qualicums were a Euclataw sept and the Haidas took their revenge on them.

“Gradually, her voice became weaker and weaker, her breathing more labored and finally, she became insensible and even as Horne looked at her, her eyes became fixed, her jaw dropped and she died…

“Life was very tough for the early ‘First Nations’ {sic, ‘Indians’} & Native warfare was even tougher…”

–‘Qualicum Massacre’,

Ben Hughes, from the 1971 book entitled, “Century of Adventure“

https://www.qualicumbeach.com/history-and-heritage

“For the actual eyewitness account of the gruesome massacre at Qualicum River, I refer to Dr. W.W. Walkem’s book “Early Stories of British Columbia“:

“Roderick Finlayson, who was the Hudson’s Bay Company official in charge of Fort Victoria, sent word asking Mr. Adam Grant Horne to call on him at Victoria; the year was 1856. Mr. Finlayson showed him a rough sketch of the east coast of Vancouver Island, pointing out a creek a short distance north of Nanaimo. This creek, he called the Qualicum … Mr. Finlayson was anxious to ascertain whether a trail existed from the Qualicum to the head of Barkley Sound and that he had selected him, Mr. Horne, to head a small expedition to proceed to the creek, interview the Indians there, and if a trail existed, ask their permission to use it…

“Finlayson selected two of his men, a French-Canadian named Cote, a good canoe-man and who knew the waters of the coast very well. He was invaluable in a crisis and who did not know what fear meant. The other man was to serve as interpreter, named Lafromboise. He also was a good canoe-man. Mr. Horne does not name the men he selected but one was an Iroquois Indian…

…

“With sail hoisted, they bowled along all day at a good clip … Leaving Nanaimo, they had a stiff southerly breeze at their backs … At 2.30 a.m., they ran on a mud flat which Cote said was near the mouth of a river about five miles south of Qualicum. They got off safely and next landed on a rough beach during a gale…

“About 6 a.m. the Iroquois aroused Mr. Horne; he had been watching a large fleet of northern canoes. He anticipated trouble. All were soon spying from the edge of the timber. They saw the canoes enter the creek, one after the other, and disappear behind the bushes that boarded the stream. They ate a hurried breakfast and waited for developments. Soon, volumes of smoke arose from the creek. It was about noon when the first canoe came back into view.

“We were horrified at the antics of these demons in human shape as they rent the air with their shouts and yells. One or two of these manning each canoe would be standing upright, going through strange motions and holding a human head by the hair in either, or both, hands. There was a very strong wind and a very rough sea while this was going on. Heading their canoes to the south and hoisting mats for sail, they passed out of site in about an hour’s time.”

“After lying concealed another hour or so, they once more launched the canoe, loaded it with the supplies and impedimenta, and poled their way along the shallow beach towards the creek. On account of the approach being shallow, a detour was made to enter the creek from the north …

“Rounding the point a few minutes later, they witnessed the result of the frightful massacre. The rancherie was a blackened heap, with smoke pouring from it. Horror of horrors! Every trunk was naked and headless and fearfully mutilated……..some of my men were for returning to Victoria, but this I positively refused to do.”

“After much searching for hiding natives, they heard one old woman by the water, moaning. She was badly wounded. She told them of the Haidas’ raid. They had taken two young women, four little girls and two small boys away with them. The old woman died shortly afterwards.

“This camp, with its headless bodies, was no place for us, so we returned to our canoes and left the creek as we had entered it, paddling two miles up the coast.”

…

“The trail at the foot of the mountain led directly to saltwater. Their arrival produced great excitement among the Indians; shouting amongst the trees by the Indians went on. They kept out of site. Soon, an arrow lodged in a tree, close to Mr. Horne’s head. They kept under close cover from here on. Shouting now came from the other side of the narrow canal, when two Indians came into view, gesticulating and brandishing weapons. The interpreter, Lafromboise, was not able to converse with them.

“Horne, taking off his pack and putting some knick-knacks in a bag, advanced to the water’s edge. After some pantomiming with their hands and arms, the natives consented to let the party cross over … A few trinkets as mirrors were thrown to the natives; these were examined with wonder. Then biscuits, but not before Horne had taken a bite out first, would they eat them. Then knives, they were a big hit. Cote asked if anyone spoke the Songhee language. A young man about eighteen years came forward, and advised them they were the first strangers they had seen, and they were afraid. The boy explained he had been captured some years ago and held prisoner.

“The rancherie was situated some distance from the saltwater canal. But Horne and his party visited the chief there. They were well armed, but the Indians tried to steal the bag of goods. The chief was asked to make the natives behave or there would be trouble. He gave the chief a blanket as a present from the Company who traded furs. The young Songhee then asked to be taken back to Victoria. Taking the chief to one side, a bargain was made to have the boy delivered at the foot of the mountain trail that evening, when he would be taken in exchange for two more blankets. The blankets and other supplies had been left far back on the trail…

“When Horne and his men returned to camp from their walk, the chief or headman came in, accompanied by the Songhee boy. The chief demanded an extra blanket. This was refused. point-blank. He was about to take the boy away back with him, when Cote pushed the boy amongst the party. They threw the two blankets to the chief, and motioned him to push-off. The boy warned that the Indians would be back with more men, and kill them all. They did return in a great state of excitement. Cote fired a volley over the natives’ heads and they fled in panic.

…

“During the course of the second afternoon of our journey southward, we turned into the mouth of Nanaimo River, and were accorded a friendly reception by the Nanaimo Indians.”

…”

–‘The Life of Adam Grant Horne’,

William Barraclough, Nanaimo Historical Society Fonds – Series 2 Sound Recordings

Transcribed by Glenys Wall, October 2004:

“The name Qualicum means “Where the Dog Salmon Run” in the Pentlach language.”

https://www.qualicumbeach.com/history-and-heritage

See also:

‘What Happened To The ‘Neutrals’?‘:

‘What Happened To The ‘Neutrals’?‘:

“This is the tribe that occupied southwestern Ontario until the 1650s, when fellow Iroquois tribes from what is now the U.S. rendered them extinct. In modern terminology, they were ‘victims of genocide’…”

https://endracebasedlaw.wordpress.com/2016/08/23/what-happened-to-the-neutrals/

“The Thule (ancestors of today’s Inuit), originally from Siberia, were gradually expanding across the Arctic, displacing the older, aboriginal Dorset people. By roughly 1200 AD, the Dorset had vanished, killed off in warfare with the Thule… Inuit oral traditions tell of how the Dorset were a gentle people without bows and arrows, and thus easy to kill and drive away…”

https://endracebasedlaw.com/2019/08/05/the-genocide-of-the-dorset/

‘The Kwantlen vs. The Yucultas’:

‘The Kwantlen vs. The Yucultas’:

“Raids by these people, called the Yucultas at the time — called the We Wai Kai now {Quadra Island, B.C.} — were the greatest fear of all along the Fraser. To say what they did to their captives, is to invite cancellation here on ‘Twitter’. But they did some bad stuff.”

https://endracebasedlaw.wordpress.com/2022/10/12/the-kwantlen-vs-the-yucultas/

“According to our ‘oral history’, we {Rocky Mountain Nakoda} were the “primary” people. All other people were “secondary”. When certain situations arose, those among the “secondary” that were considered enemies…were to be wiped out by whatever means necessary. Historically, we are also called by the more formidable name of…“Head Decapitators”. The mere mention of the name…issued a warning to the warring enemies of what was to transpire…”

–‘Rocky Mountain Nakoda – Who We Are’

http://endracebasedlaw.ca/2018/10/26/finally-some-honesty/

‘What’s In A Name?’ (Tofino):

“I love it when they do land acknowledgements in Tofino, whose ‘Indigenous’ name is ‘Esowista’, which means:

“Captured by clubbing the people who lived there to death.”

https://endracebasedlaw.ca/2022/10/20/whats-in-a-name/

History Moment: ‘Champlain’s Fight With the Iroquois, 1609’:

“Champlain had to make friends of the Algonquin and Huron Indians around him so that they would guide him into this unknown land, and allow him to make settlements and build trading posts among them. To gain their good-will he had to promise to help them in their war with the Iroquois south of the lakes, who were their deadly enemies. So it was in the summer of 1609, the next after the founding of the city of Quebec, that Champlain joined a party of his Indian allies on a raid into the Iroquois country…”

https://endracebasedlaw.ca/2019/08/25/history-moment-champlains-fight-with-the-iroquois-1609/

♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠

Websites:

END RACE BASED LAW inc. Canada

https://endracebasedlaw.wordpress.com/

ERBL Canada Daily News Feed Blog

https://endracebasedlawcanadanews.wordpress.com/

♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠

Facebook:

ERBL Main Page

https://www.facebook.com/ENDRACEBASEDLAW

ERBL Canada Daily News Feed Blog

https://www.facebook.com/groups/ENDRACEBASEDLAWnewsCanada

♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠

TWITTER (X): https://twitter.com/ERBLincCanada

♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠

Petition to END RACE BASED LAW

https://endracebasedlaw.wordpress.com/petition-canada/

JOIN US IN THE FUTURE OF A UNIFIED CANADA